On the 150th Year of “Vande Mataram,” Why Do Disputes Still Persist?

Maguni Charan Behera

Maguni Charan Behera

Chief Editor, Sampratyaya (www.sampratyaya.com)

Email: sampratyaya.ijr@gmail.com

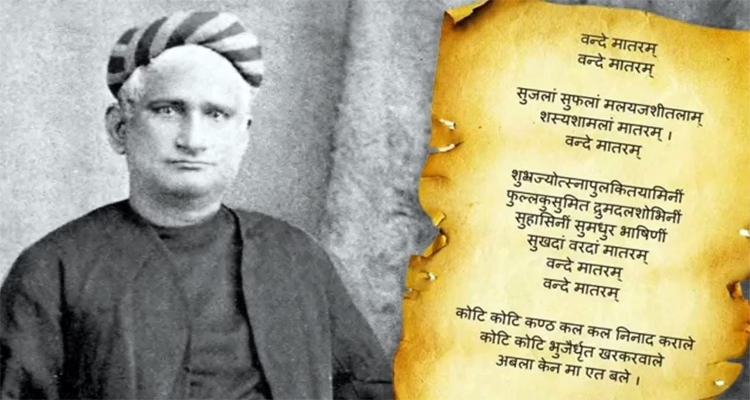

Few expressions in modern Indian history carry the emotional weight, cultural depth, and political symbolism of Bande Mataram. Emerging from Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Anandamath, it evolved from a literary invocation into the primary rallying cry of India’s anti-colonial struggle. Revolutionaries shouted it on their way to the gallows; mass processions sang it in defiance of British rule; the colonial state banned it repeatedly. In time, it became inscribed into the emotional landscape of the freedom movement.

Yet, despite this rich history, objections persist—even today—against its recital on national platforms. These objections often stem from misunderstandings of India’s cultural traditions, historical evolution, and the context in which the slogan emerged.

The phrase Bande Mataram predates modern political controversies. It draws from deep civilizational values shared across India’s diverse communities. Those who oppose it—especially from narrow political or religious standpoints—often overlook the indigenous worldview and cultural depth from which the phrase was born.

This raises several questions:

Is the slogan religious? Does it insult any faith? Why was it opposed historically? And are those objections meaningful today?

To answer these, one must move beyond contemporary political commentary and return to India’s civilizational foundations—the ancient Earth-as-Mother tradition, the historical circumstances of its emergence, and the political motivations behind early 20th-century objections. Only then can one recognise how certain objections persist today unchanged, without intellectual evolution.

Before Christianity and Islam, All Cultures Considered Earth as Mother

The idea of Earth-as-Mother is not a religious command but a civilizational expression. It is older than Islam and Christianity, embedded deeply within India’s tribal, regional, and classical cultures.

Long before Vedic culture and formalised religion, indigenous communities revered Earth as Mother:

- Santhals: Jaher Ayo (Mother of the Grove)

- Gonds: Dharti Mata

- Oraons: Atma Devi / Rohi Mata

- Nagas: Land as a maternal life-giver

- Bhils: Kali Maa as Earth Mother

This reverence is ecological and civilisational, not doctrinal. The Earth feeds, sustains, carries and shelters—therefore she is Mother.

Likewise, pre-Islamic and pre-Christian civilizations—Greek, Roman, Sumerian, African, Native American—personified Earth as Mother:

- Gaia (Greek)

- Terra Mater (Roman)

- Ki (Sumerian)

Thus, Earth-as-Mother is a universal metaphor of gratitude, not idol worship.

In Indian cultural continuity, the land is mother across languages—Bharat Mata, Matrubhoomi, Janani Dharti, Thaaimann, Maati Amru. When Bankim wrote “Vande Mataram,” he drew from a sentiment older than all organised religions.

Context of Bande Mataram in the Freedom Struggle

The phrase Bande Mataram must be understood within the historical context that gave it meaning. It emerged not from religious ritual but from the centre of anti-colonial resistance.

During the 1905 Swadeshi Movement, after the partition of Bengal, it became the heartbeat of India’s first major mass mobilisation against British rule. Its emotional force grew so powerful that the British banned it—turning it into a forbidden hymn of defiance.

Revolutionaries embraced it:

- Khudiram Bose

- Bagha Jatin

- Bhagat Singh

- Chittagong Armoury revolutionaries

For them, saluting the “Mother” was not a theological act but a vow of political courage, dignity, and unity.

Long before the freedom struggle, the idea of land as mother carried no religious compulsion. It was simply part of India’s cultural imagination.

Muslim Participation and Acceptance

Prominent Muslim leaders and revolutionaries accepted, used, or defended the slogan:

- Maulana Abul Kalam Azad called it patriotic, not theological

- Maulana Hasrat Mohani sang it at Congress sessions

- Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan and Khudai Khidmatgars used it

- Rafi Ahmed Kidwai, Asaf Ali, Syed Hasan Imam, Hakim Ajmal Khan joined gatherings where it was sung

- Maulana Barkatullah Bhopali used it abroad while mobilising support

Their acceptance shows that Bande Mataram was never viewed as a religious imposition but as a unifying patriotic call.

Jinnah’s Objection: A Strategy of Political Separation

Muhammad Ali Jinnah initially had no objection to Hindu cultural expressions. He even joined Congress prayer meetings in the early years. His objections to Bande Mataram arose only after 1937, when the politics of separate Muslim identity became central to the Pakistan project.

The logic behind his objection:

- A distinct nation requires distinct symbols

- Shared cultural expressions undermine the two-nation theory

- A symbol of unity had to be rejected to argue for separation

Thus, his objection was strategic, not spiritual.

Once Pakistan was created, that logic ended. Indian Muslims today are citizens of a secular republic; objections born from pre-Partition political strategy cannot define post-Independent India’s cultural discourse.

Theological and Constitutional Clarifications

Critics claim the phrase is “not in Islam.” That is true—but irrelevant. India is not governed by the theology of any single religion.

Islam forbids polytheism, not metaphor.

Islamic culture uses metaphors such as:

- Umm-al-Qura — Mother of Cities (Mecca)

- Umm-al-Kitab — Mother of the Book

- Umm — Mother as origin

Calling one’s land “mother” cannot violate monotheism.

Constitutional Settlement

The Constituent Assembly debated the issue:

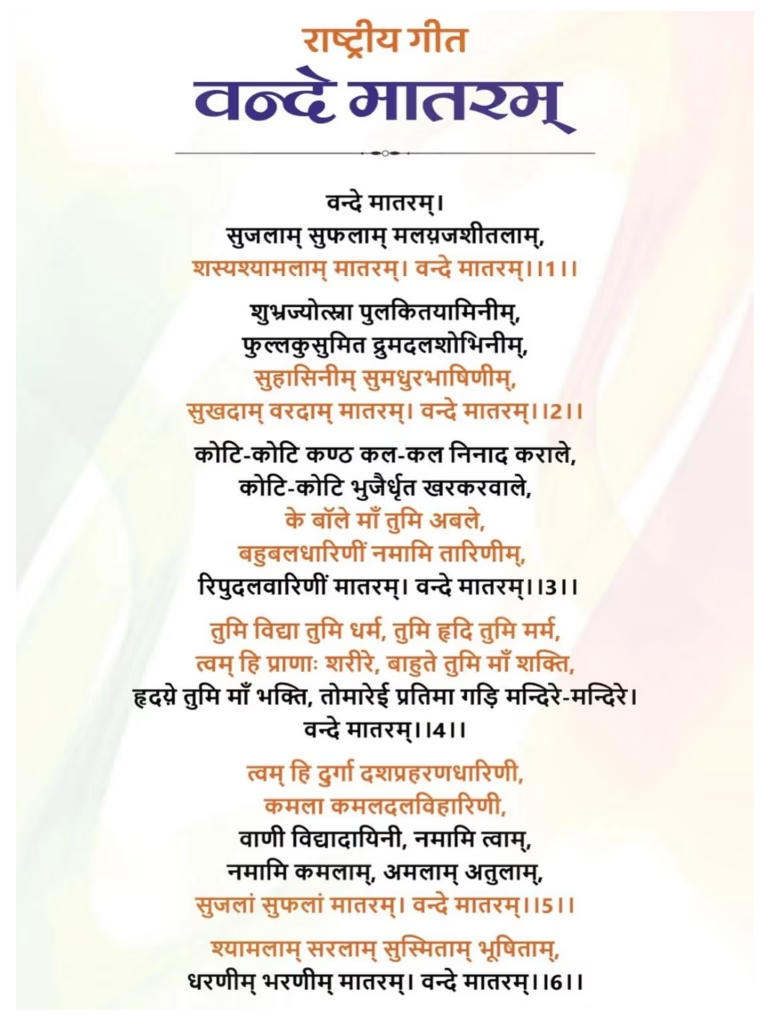

- Jana Gana Mana → National Anthem

- Bande Mataram → National Song

- Only first two stanzas adopted (purely patriotic)

- No citizen can be compelled to sing it

Therefore:

- No compulsion exists

- No theological violation exists

- No religious freedom is infringed

Alternatives and the National Question

Should India adopt a new slogan?

A diverse, multi-civilizational nation cannot adopt symbols rooted in one religion. Neutral slogans lack emotional force; religious slogans alienate others. Bande Mataram occupies a unique middle space:

- rooted in culture

- older than organised religion

- emotionally powerful

- born from mass struggle

- unifying across communities

Mother as Sustainer, Preserver, Controller of Evil

The metaphor of mother expresses universal values: sustenance, protection, moral guidance, and care. These qualities belong to no religion—they are human values.

Viewing the nation as mother signifies duty and responsibility, not deity worship. Interpreting this metaphor literally is a misunderstanding of poetry, history, and culture.

Why Object Today?

There are only three possible reasons:

- Theological misunderstanding

– confusion between metaphor and worship - Political identity mobilisation

– obsolete after Pakistan’s creation - Psychological prioritisation of religious identity above national identity

None of these reasons are philosophically, culturally, or historically sound.

Does Bande Mataram Offend Any Religion?

The answer is No.

A cultural metaphor cannot offend a religion simply because that metaphor is absent in its theology. National respect and religious practice operate in different domains.

Muslims who fought for India’s freedom sang Bande Mataram without feeling any conflict with their faith.

The objection is modern and political—not timeless or religious.

Is There Any Better Slogan Than Vande Mataram?

No alternative captures:

- India’s civilizational depth

- ecological intimacy

- emotional resonance

- historical significance

- anti-colonial spirit

Neutral slogans lack depth. Religious slogans exclude. Bande Mataram remains unmatched.

Conclusion

The debate around Bande Mataram cannot be understood without acknowledging:

- the universality of Earth-as-Mother

- its revolutionary origins

- the political motivations of early objections

- the changed realities after Partition

- constitutional clarity on freedom

There is no intrinsic religious offence in the phrase. Early objections were political, not theological, and hold no validity today.

India’s nationhood draws from a civilizational well deeper than any organised religion. The land has always been mother—to tribes, communities, and civilizations—long before theological boundaries existed.

Bande Mataram is not a command, compulsion, or doctrine. It is a poetic, patriotic declaration of love for the land—one that shaped India’s freedom struggle and continues to represent the enduring responsibility to protect and serve the nation.