Maguni Charan Behera

Chief Editor, Sampratyaya (www.sampratyaya.com)

Email: sampratyaya.ijr@gmail.com

Introduction

The Babri Masjid–Ram Janmabhoomi dispute is one of the most emotionally charged and politically defining episodes in modern India. It is not just a clash over land or architecture; it is a window into the country’s complex layers of history, identity, and constitutional values. The issue brings together memories of medieval power struggles, colonial strategies, modern identity politics, and the challenges of building a cohesive nation out of immense diversity.

This essay revisits the history of the Babri Masjid, examines the roles played by political leaders like Rajiv Gandhi, P. V. Narasimha Rao and Mulayam Singh Yadav, and revisits the circumstances that led to the demolition. It also studies the narratives promoted by the BJP and other groups. More importantly, it reflects on deeper questions: Should medieval episodes dictate the politics of a modern republic? Should communities stay confined within the wounds of history? And does a religious community lose something essential when a medieval-era structure no longer stands?

Historical Origins: The Babri Masjid and Its Symbolism

A Structure of Power, Not Theology

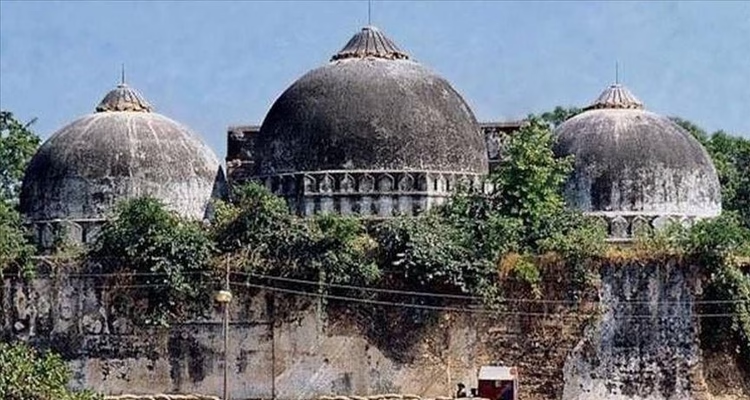

The Babri Masjid was built in 1528 during the reign of Babar. Interestingly, it was not named after a spiritual figure or Quranic concept, as many Islamic religious structures typically are. It carried the name of a ruler—a political authority—which indicates that the construction may have served more as a symbol of imperial presence than religious devotion. Many medieval structures represented political dominance rather than purely spiritual purpose.

The Question of a Pre-Existing Temple

Archaeological debates have long revolved around whether a temple stood on the site before the mosque. The ASI’s 2003 findings pointed to the remains of a large Hindu religious structure predating the mosque. In the medieval era, the destruction or alteration of local temples often accompanied political expansion. Such acts reflected conquest and authority—not necessarily religious hostility.

In this light, the Babri Masjid is frequently seen by scholars as a symbol of political control. Thus, the call to replace it was not simply religious retaliation—it carried a cultural desire to restore continuity with the region’s pre-conquest identity.

Sentiments and Identity: Why the Site Matters

For Hindus, Ayodhya has been associated with the birthplace of Lord Rama for centuries—long before the modern political dispute. The belief finds mention in the Puranas, medieval devotional literature, and Ram bhakti traditions led by saints like Tulsidas and the Ramanandi sadhus.

For millions of Hindus, the site represents:

- Deep emotional connection

- Cultural belonging

- Historical and civilisational pride

To many, the Babri Masjid’s presence on that site symbolised a painful legacy of conquest. For local Muslims, however, it was simply a place of worship and part of their lived religious experience.

The tragedy was that the two narratives confronted each other without any effective mechanism of reconciliation.

Political Leadership and the Shaping of the Conflict

The dispute’s political journey has been driven as much by electoral strategies as by historical claims.

Rajiv Gandhi’s Calculated Balancing

In 1986, the Rajiv Gandhi government ordered the unlocking of the disputed site for Hindu worship. In 1989, it allowed the shilanyas. Coming shortly after the Shah Bano controversy, these steps were widely seen as an attempt to balance political constituencies. Instead, they turned a local dispute into a national movement.

Mulayam Singh Yadav’s Opposite Stand

In 1990, as Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister, Mulayam Singh took a hardline position to stop kar sevaks from reaching the site. The police firing that killed several protesters aggravated the divide further: many Hindus saw it as suppression of faith, while many Muslims saw Mulayam as a protector of their rights.

The 1992 Demolition and the Rao Government

On 6 December 1992, during P. V. Narasimha Rao’s term as Prime Minister, the mosque was torn down by a mob. It was an unlawful act, a national embarrassment, and a devastating blow to India’s social fabric. It exposed failures of governance and the dangers posed by political hesitation.

Secularism, in spirit, is meant to protect all communities equally. Yet in this case, critics argue that governments emphasised protecting the mosque without adequately addressing the deep historical grievance felt by many Hindus. The Liberhan Commission later blamed political leaders across parties for letting the situation spiral.

The BJP’s Narrative and Mobilisation

The BJP and its allied groups built their campaign on three major claims:

- A historical wrong had to be corrected.

- Hindu pride had to be restored.

- A sacred birthplace had to be reclaimed.

According to this narrative:

- The mosque was erected over a demolished temple.

- India’s civilisational heritage must be acknowledged.

- Building a temple was a cultural duty, not just a political demand.

This message resonated widely, particularly in North India, propelling the BJP from a marginal party in 1984 to a national force by the 1990s. Regardless of one’s stance, the mobilisation demonstrated the political power of cultural memory.

Was the Demolition Religious or Simply Vandalism?

To assess the demolition’s nature, theological principles must be separated from political legacies.

- Islamic theology does not require preservation of a medieval-era mosque if it disrupts social peace.

- A mosque’s sanctity comes from prayer—not from who built it or why.

- The Babri Masjid was tied more to Babar’s political legacy than to Islam’s spiritual core.

Likewise, the demolition by a mob was not dharmic or ethical. If the mosque was built after destroying a temple, that act was wrong. Bringing down the structure unlawfully was also wrong. Both moments represent violations of justice.

True reconciliation required a legal and peaceful path, not retaliation.

The 2019 Supreme Court Verdict: A Constitutional Settlement

The Supreme Court’s 2019 judgment attempted to close a centuries-old wound through constitutional reasoning.

The Court:

- Declared the 1992 demolition illegal

- Accepted archaeological evidence of a pre-existing temple

- Recognised the Hindu claim as rooted in long-standing belief

- Allotted 5 acres of land to Muslims for a new mosque

It neither idealised history nor delegitimised faith. It offered a practical and fair settlement. Today, the Ram Mandir stands at the disputed site, and the new mosque is taking shape nearby—two structures coexisting as symbols of India’s plural ethos.

Should Medieval Wounds Shape Modern Politics?

This is the central philosophical question.

History offers lessons, not templates.

India cannot afford to replay medieval conflicts in modern times.

- We cannot return to the age of Babar.

- Modern Indian Muslims have no connection to Babar.

- Their future must rest on education, economic opportunity, and dignity, not medieval memories.

A community’s identity should not be confined to the survival of one medieval monument.

Similarly, Hindu identity must not be built solely on reenacting past traumas.

Does Islam Lose Anything Without the Babri Masjid?

Islam is a global, universal faith that transcends geography.

- Faith lives in people, not in any one structure.

- Mosques can be built anywhere.

- The Quran does not attach sanctity to political monuments.

The Muslim community’s long-term progress will not be defined by the Babri structure but by empowerment, education and inclusion.

A Mature Path for India

India must transform painful memories into opportunities for harmony.

For the Muslim Community

Future-oriented progress requires:

- Modern and higher education

- Entrepreneurship

- Digital skills

- Women’s empowerment

- Social mobility

Fixation on medieval symbols does not help long-term development.

For the Nation as a Whole

India’s identity draws from:

- Ancient heritage

- Medieval cultural exchange

- Freedom struggle

- Constitutional values

The Ram Mandir and the new mosque should not become rival symbols but complementary ones—representing coexistence.

Lessons for Political Leadership

The Babri dispute teaches that:

- Populism intensifies conflicts

- Electoral balancing acts can inflame tensions

- State violence deepens divides

- Inaction at critical moments can cause lasting damage

Leaders must uphold constitutional morality, avoid appeasement of any community, encourage dialogue, and prioritise development as the real cement of national unity.

Conclusion: A Shared Past, A Shared Future

The Babri Masjid–Ram Janmabhoomi issue is no longer a matter for courts. It is now a test of India’s collective maturity. Can the country accept its complicated past without allowing it to divide the present? Can faith be celebrated without hurting another? Can we transform conflict into reconciliation?

If India draws the right lessons, this episode will ultimately be remembered not for destruction, but for resolution. The Ram Mandir and the new mosque can stand not as markers of division but as symbols of a civilisation capable of healing itself.

The dispute has reached legal closure. The responsibility now lies with society and leadership to move from memory to maturity, and from symbolism to shared development.